Arunachala Gounder (Dead) by LRs. v. Ponnusamy & Ors., 2022 (SC) 71

BENCH: – S. Abdul Nazeer J., Krishna Murari J.

Facts of the Case

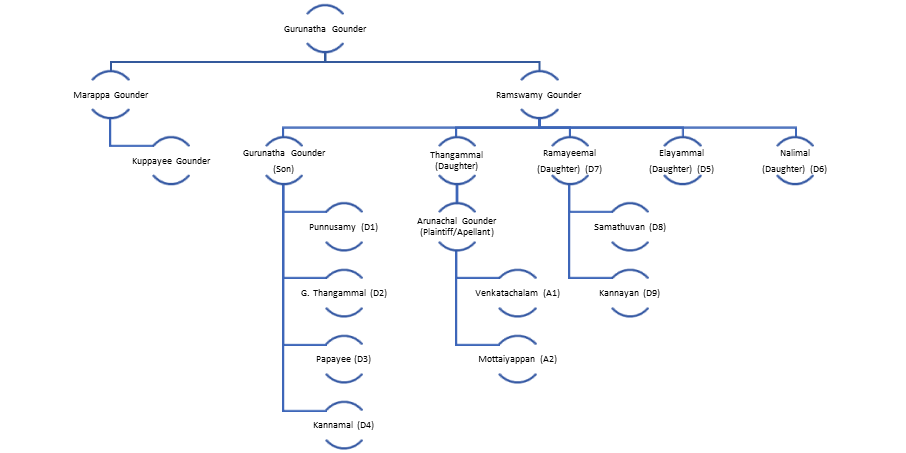

Marappa Gounder, who passed away and left only his daughter Kuppayee Ammal remaining, obtained the suit property on his own. After Marappa Gounder passed away and left no heirs, Kuppayee received his estate. The younger brother of Marappa Gounder, who died before Marappa, was Ramasamy Gounder. The five heirs of Ramasamy Gounder received a part of the suit property in an amount equal to one fifth when Kuppayee passed away. The Ramasamy’s son Gurunatha Gounder and his four legal heirs and representatives were among the five heirs.

The family genealogy is represented in the chart shown below

The daughter of Ramasamy, Thangammal, filed the partition lawsuit before the Trial Court. The parties agreed that Marappa independently acquired the suit property through a court auction process. The Trial Court came to the conclusion that Marappa passed away in 1949, the property in question would pass to the lone son of the dead Ramasamy Gounder by survivor’s rights, and the plaintiff had no standing to bring the complaint for partition. After dismissing the partition claim, the High Court of Madras upheld the ruling on the first appeal, deciding that the case will proceed according to survivorship. The appellant petitioned the Apex Court in this case after feeling wronged by the ruling.

Issues

- What is the nature and course of a succession of the suit property?

- Whether a Hindu daughter could inherit her father’s separate property who died intestate before the enactment of the Hindu Succession Act of 1956?

- What would be the manner of succession of the suit property after the death of such daughter?

Arguments by the Appellant

The Appellants argued that Marappa Gounder acquired the property on December 15, 1938, in a court auction sale, making it his independent property. As a result, the aforementioned independent property was never regarded as joint family property and would pass to his daughter through succession. It was argued that this would be in line with the Law of Mitakshara, according to which inheritance laws are dependent on closeness of kinship.

The appellants also argued that according to Hindu Law, a daughter is not ineligible to inherit her father’s separate property. It was argued that if a Hindu man only leaves behind a daughter, his separate property would pass to the daughter through succession rather than the brother’s son through survivorship.

Arguments by the Respondent

The respondents argued that the property in question was acquired by Marappa Gounder through a court-ordered sale but using family funds, making it a shared family asset. Accordingly, it was argued that Ramasamy Gounder’s son received the land as a co-heir after Marappa Gounder passed away without leaving a male successor.

The respondents added that Marappa Gounder’s passing had been verified in 1949. As a result, the succession to his holdings would begin in 1949 when Kupayee Ammal, the daughter of Marappa Gounder, lost her right to inherit her father’s estate. The property thus passed to Ramasamy Gounder’s son.

Judgment

The Supreme Court upheld the appeal, noting that Marappa Gounder had admittedly bought the suit property on his own, despite the family being joined at the hip at the time of his intestate death. As a result, Kupayee Ammal, his lone surviving daughter, would receive the land via inheritance and not through survivorship.

The Supreme Court came to this conclusion after consulting both traditional Hindu law and judicial rulings, noting that both the old traditional Hindu law and numerous judicial rulings recognise a widow’s or daughter’s right to inherit the self-acquired property or share received in the division of a coparcenary property of a Hindu male dying intestate.

To hold that a daughter was capable of inheriting her father’s separate property as per customary Hindu Law, the Supreme Court observed the following:

The Bombay School of Law: The heritable capacity of a large number of female heirs is also recognised by the Bombay school of Law, including a half -sister, father’s sister and women married into the family such as stepmother, son’s widow, brother’s widow and also many other females classified as “bandhus.”

The Supreme Court also considered the legislative modification brought about by the 1956 Act. The purpose of Section 14(I) of the 1956 Act, it was noted, was to address the restriction placed on Hindu women, who were not previously entitled by law to claim an absolute interest in the possessions she inherited. Her claim was therefore restricted to just a life interest in the assets she had so inherited. The Supreme Court stated that while Kupayyi Ammal passed away in 1967, a long time after the 1956 Act was passed, the succession sequence following her death will follow the 1956 Act.

The Supreme Court also explained the structure of Section 15 of the 1956 Act’s sub-section (2). According to what has been seen, if a female Hindu passes away intestate without any children, the property she inherited from her parents would pass to the heirs of her father, while the property she inherited from her husband or father-in-law would pass to the heirs of the husband. Therefore, the main goal of the Legistaure is to make sure that the inheritance of a female Hindu who passes away without having children or leaving a will goes back to the source. As a result, Thangammal (and the other daughters of Ramasamy Gounder) were determined to have a right to a one-fifth share in the suit property.

WRITTEN BY:

Shivanshu Gupta

LL.B. (4th Semester)

LLOYD SCHOOL OF LAW

Yet another Lawyer who happens to indulge in the gratification of reading and writing the Language of Law.

Yet another Lawyer who is trying to be better than yesterday.

Well explained…!

Good

Well written 👍🏻

Good good very good….. Keep it up brother !!!

Well explained..!!